Length- 40km

Route- From the Hills Motorway (M2) and Old Windsor Road (A2) at Seven Hills, travelling in a westerly direction before turning south at Dean Park, to the South-Western Motorway (M5) and Hume Motorway (M31) at Prestons.

Route Number- M7

Width- Seven Hills to Prestons- Two Lanes

Opening- 16th December 2005

Cost- $1.65 billion ( $200 million from NSW Government, $1.5 billion from Federal Government)

Toll- Distance-based- 40.4c per km (capped after 20km at $8.08 as of August 2018)

The Westlink M7 is a 40km tolled motorway linking the M2 at Seven Hills to the M4 at Eastern Creek, the M5 at Prestons, and everywhere in between.

Before opening, traffic entering the city via the Hume Highway from the south or the F3 Sydney-Newcastle Freeway (now M1 Pacific Motorway) from the north was required to negotiate the heavily trafficked Cumberland Highway. On opening in 2005, the M7 Westlink allowed traffic to bypass the Sydney suburbs altogether via a two-lane dual-carriageway link, directing traffic across the furthest suburban fringes of the city to the west.

The M7 Westlink is notoriously one of the least congested motorways in Sydney, with virtually free-flowing traffic on a majority of its route at all times of the day. Despite this, the motorway is well-used, especially by industrial traffic.

Ironically, barely ten years after construction, the M7 has itself become more and more redundant as Sydney has expanded; once a bypass of Sydney’s suburbs, like the Cumberland Highway it too has increasingly become a key suburban route. Whilst traffic levels on the motorway are still tolerable, the government has become planning for the M9 Outer Sydney Orbital which, on opening in the distant future, could supersede the M7 Westlink as the new bypass of Sydney.

Route- From the Hills Motorway (M2) and Old Windsor Road (A2) at Seven Hills, travelling in a westerly direction before turning south at Dean Park, to the South-Western Motorway (M5) and Hume Motorway (M31) at Prestons.

Route Number- M7

Width- Seven Hills to Prestons- Two Lanes

Opening- 16th December 2005

Cost- $1.65 billion ( $200 million from NSW Government, $1.5 billion from Federal Government)

Toll- Distance-based- 40.4c per km (capped after 20km at $8.08 as of August 2018)

The Westlink M7 is a 40km tolled motorway linking the M2 at Seven Hills to the M4 at Eastern Creek, the M5 at Prestons, and everywhere in between.

Before opening, traffic entering the city via the Hume Highway from the south or the F3 Sydney-Newcastle Freeway (now M1 Pacific Motorway) from the north was required to negotiate the heavily trafficked Cumberland Highway. On opening in 2005, the M7 Westlink allowed traffic to bypass the Sydney suburbs altogether via a two-lane dual-carriageway link, directing traffic across the furthest suburban fringes of the city to the west.

The M7 Westlink is notoriously one of the least congested motorways in Sydney, with virtually free-flowing traffic on a majority of its route at all times of the day. Despite this, the motorway is well-used, especially by industrial traffic.

Ironically, barely ten years after construction, the M7 has itself become more and more redundant as Sydney has expanded; once a bypass of Sydney’s suburbs, like the Cumberland Highway it too has increasingly become a key suburban route. Whilst traffic levels on the motorway are still tolerable, the government has become planning for the M9 Outer Sydney Orbital which, on opening in the distant future, could supersede the M7 Westlink as the new bypass of Sydney.

Pre-Construction

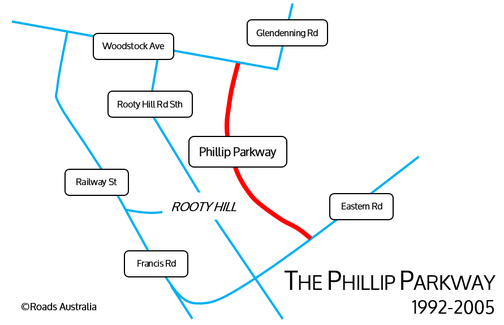

The County Of Cumberland was an important planning scheme exhibited in 1951 that outlined the routes of such key motorways as the Castlereagh Freeway (now the M2 Hills Motorway), the Western Freeway (now the M4 Western Motorway) and the South Western Freeway (now the M5 South Western Motorway). Whilst no plans for a freeway linking these three freeways existed in these plans (the corresponding F7 was instead allocated to the unconstructed Eastern Freeway), the plan for a route linking the F2 Castlereagh Freeway with the F4 Western Freeway soon emerged in the 1960s. Such a route was never seen as a priority by the government; although the F4 was eventually constructed to its full westerly extent, there existed no intention by the government to construct the F2 to its full extent. However, in the late 1980s, with the intended construction of a steel mill in Rooty Hill, the Blacktown City Council necessitated the operators of the steel mill, BHP, to construct an arterial route that allowed industrial traffic to bypass the Rooty Hill CBD. A 2km two-lane road between Woodstock Avenue and Eastern Road in Rooty Hill opened to traffic in July 1992. For a more thorough history of the Phillip Parkway, visit this page on site Ozroads.

In 1974, the Sydney Area Transportation Study proposed the need for an outer metropolitan highway, identifying the corridor for this route. The route, however, was not considered a priority by the government at the time.

The Cumberland Highway was progressively constructed in the 70s and 80s, as a route allowing traffic to pass between the Hume and Pacific Highways and thus bypass Sydney. As such, the highway bypassed the existing Woodville Road route, of which was originally assigned this purpose by the Department of Main Roads. Parts of the Cumberland Highway had already been constructed in the 1970s and 1980s as part of the Parramatta Bypass, with the route extended to its current-day entirety by 1988.

In 1987, the Roads 2000 plan was released by the Department of Main Roads. The plan outlined a proposal to construct an orbital linking all freeways in Sydney, providing a bypass of major urban centres. The following was included in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 27th March 1987; “a 93-kilometre orbital route linking all major incoming highways, a second Spit Bridge to improve traffic flow and a second Sydney Harbour crossing by the end of the century.” The plan for the orbital included the route that would become the M7 Westlink, which would connect the proposed F2 Castlereagh Freeway with the existing F4 Western Freeway and F5 South Western Freeway. However, the plan did not indicate that there was an intention to construct the M7 Westlink as a grade-separated freeway; rather, it was possible that the route would be constructed merely as an at-grade arterial, similarly to the Cumberland Highway.

As the 1990s progressed, the Government begun to express an interest in constructing a Western Sydney Orbital, as outlined in the Roads 2000 plan, as a freeway.

In 1993, the Liverpool to Hornsby Study Final Route was released, outlining a route to link the F5 at Liverpool with the F3 at Hornsby. The Action for Transport 2010 plan was released in 1998 by the NSW Government, proposing the construction of the M7 by 2007. On opening, it was intended that the M7 form a part of the National Highway Network, a now-defunct Federal program providing funding to key routes linking capital cities.

In 1994, the Australian Government announced plans to fund an environmental impact study (EIS) into the route. Shortly after, $109 million was allocated to pre-construction. In 1998, community consultation begun regarding the preliminary design for the project; as a result, several changes were made.

The EIS for the project was released by the RTA on the 8th January 2001. Over 260 submissions were made, with more modifications being made to the project, announced in November 2001. The Australian Government provided a further $360 million towards the project in 2001. Planning approval for the project was granted by the NSW Transport Minister in February 2002, and by the Commonwealth in July 2002.

The project was to be constructed as a BOOT project; Build-Own-Operate-Transfer; that is where a private entity finances, constructs and operates a project for a concession period as per a contract agreed upon with the government.

Registrations of Interest (ROI), including a detailed proposal of the project, were sought by the RTA in July 2001. A rigorous process was undertaken to choose the consortium to construct the project. By March 2002 three consortiums had submitted a proposal. The Westlink Motorway Consortium, sponsored by Leighton Contractors, Abigroup, Transurban and Macquarie Bank, was chosen to build the M7 in October 2002, with a concession period until February 2037.

More information on the pre-construction phase of the Westlink M7 can be read in this document.

The Federal Government allocated $360 million to the project, with the remaining $1.18 billion to be privately financed.

Images of the concept design for the motorway can be viewed below, accessed from the Westlink M7: Summary of Contracts, released in August 2003. This document can be viewed here.

The County Of Cumberland was an important planning scheme exhibited in 1951 that outlined the routes of such key motorways as the Castlereagh Freeway (now the M2 Hills Motorway), the Western Freeway (now the M4 Western Motorway) and the South Western Freeway (now the M5 South Western Motorway). Whilst no plans for a freeway linking these three freeways existed in these plans (the corresponding F7 was instead allocated to the unconstructed Eastern Freeway), the plan for a route linking the F2 Castlereagh Freeway with the F4 Western Freeway soon emerged in the 1960s. Such a route was never seen as a priority by the government; although the F4 was eventually constructed to its full westerly extent, there existed no intention by the government to construct the F2 to its full extent. However, in the late 1980s, with the intended construction of a steel mill in Rooty Hill, the Blacktown City Council necessitated the operators of the steel mill, BHP, to construct an arterial route that allowed industrial traffic to bypass the Rooty Hill CBD. A 2km two-lane road between Woodstock Avenue and Eastern Road in Rooty Hill opened to traffic in July 1992. For a more thorough history of the Phillip Parkway, visit this page on site Ozroads.

In 1974, the Sydney Area Transportation Study proposed the need for an outer metropolitan highway, identifying the corridor for this route. The route, however, was not considered a priority by the government at the time.

The Cumberland Highway was progressively constructed in the 70s and 80s, as a route allowing traffic to pass between the Hume and Pacific Highways and thus bypass Sydney. As such, the highway bypassed the existing Woodville Road route, of which was originally assigned this purpose by the Department of Main Roads. Parts of the Cumberland Highway had already been constructed in the 1970s and 1980s as part of the Parramatta Bypass, with the route extended to its current-day entirety by 1988.

In 1987, the Roads 2000 plan was released by the Department of Main Roads. The plan outlined a proposal to construct an orbital linking all freeways in Sydney, providing a bypass of major urban centres. The following was included in the Sydney Morning Herald on the 27th March 1987; “a 93-kilometre orbital route linking all major incoming highways, a second Spit Bridge to improve traffic flow and a second Sydney Harbour crossing by the end of the century.” The plan for the orbital included the route that would become the M7 Westlink, which would connect the proposed F2 Castlereagh Freeway with the existing F4 Western Freeway and F5 South Western Freeway. However, the plan did not indicate that there was an intention to construct the M7 Westlink as a grade-separated freeway; rather, it was possible that the route would be constructed merely as an at-grade arterial, similarly to the Cumberland Highway.

As the 1990s progressed, the Government begun to express an interest in constructing a Western Sydney Orbital, as outlined in the Roads 2000 plan, as a freeway.

In 1993, the Liverpool to Hornsby Study Final Route was released, outlining a route to link the F5 at Liverpool with the F3 at Hornsby. The Action for Transport 2010 plan was released in 1998 by the NSW Government, proposing the construction of the M7 by 2007. On opening, it was intended that the M7 form a part of the National Highway Network, a now-defunct Federal program providing funding to key routes linking capital cities.

In 1994, the Australian Government announced plans to fund an environmental impact study (EIS) into the route. Shortly after, $109 million was allocated to pre-construction. In 1998, community consultation begun regarding the preliminary design for the project; as a result, several changes were made.

The EIS for the project was released by the RTA on the 8th January 2001. Over 260 submissions were made, with more modifications being made to the project, announced in November 2001. The Australian Government provided a further $360 million towards the project in 2001. Planning approval for the project was granted by the NSW Transport Minister in February 2002, and by the Commonwealth in July 2002.

The project was to be constructed as a BOOT project; Build-Own-Operate-Transfer; that is where a private entity finances, constructs and operates a project for a concession period as per a contract agreed upon with the government.

Registrations of Interest (ROI), including a detailed proposal of the project, were sought by the RTA in July 2001. A rigorous process was undertaken to choose the consortium to construct the project. By March 2002 three consortiums had submitted a proposal. The Westlink Motorway Consortium, sponsored by Leighton Contractors, Abigroup, Transurban and Macquarie Bank, was chosen to build the M7 in October 2002, with a concession period until February 2037.

More information on the pre-construction phase of the Westlink M7 can be read in this document.

The Federal Government allocated $360 million to the project, with the remaining $1.18 billion to be privately financed.

Images of the concept design for the motorway can be viewed below, accessed from the Westlink M7: Summary of Contracts, released in August 2003. This document can be viewed here.

Construction

Construction on the Westlink M7 begun in July 2003. Key construction activities progressed through to the end of 2003, including:

A total of 18 interchanges were required by the project. This included an interchange between the new motorway and the existing M4 Motorway. The nature of traffic in the area demanded that the interchange be constructed as a complete four-level stack interchange (for more on interchanges read here). Such an interchange was incredibly demanding to coordinate and construct, especially given that the new M7 motorway was being constructed over a motorway that was not to be closed for the duration of construction. The construction of the interchange involved 18 bridges; the northbound bridge carrying traffic over the M4 was 431m, with the southbound bridge 397m. It was decided that the interchange be named the Light Horse Interchange, with a 55m tower in the centre of the interchange resembling a torch, in honour of the Light Horse Brigade that fought at Gallipoli. The brigade trained nearby at a training base off Wallgrove Road. A very impressive time-lapse featuring the construction of the Light Horse Interchange can be viewed below.

Construction on the Westlink M7 begun in July 2003. Key construction activities progressed through to the end of 2003, including:

- Building temporary roads to access the Westlink M7 corridor

- Constructing storm water detention basins

- Constructing bridges

- Hauling fill material to sites using arterial roads

- Relocating and upgrading utilities

- Building construction compounds

- Clearing, earthworks and installing drainage

- Removing existing structures

A total of 18 interchanges were required by the project. This included an interchange between the new motorway and the existing M4 Motorway. The nature of traffic in the area demanded that the interchange be constructed as a complete four-level stack interchange (for more on interchanges read here). Such an interchange was incredibly demanding to coordinate and construct, especially given that the new M7 motorway was being constructed over a motorway that was not to be closed for the duration of construction. The construction of the interchange involved 18 bridges; the northbound bridge carrying traffic over the M4 was 431m, with the southbound bridge 397m. It was decided that the interchange be named the Light Horse Interchange, with a 55m tower in the centre of the interchange resembling a torch, in honour of the Light Horse Brigade that fought at Gallipoli. The brigade trained nearby at a training base off Wallgrove Road. A very impressive time-lapse featuring the construction of the Light Horse Interchange can be viewed below.

The pavement used for the road surface on the M7 was developed by the University of Western Sydney and the design team, allowing continuous reinforced concrete to be used on the motorway. The design choice ensured that a reduction in noise and maintenance costs for the motorway.

In alignment with the construction of the M7 Westlink, several roads had to be upgraded. These included (accessed from Ozroads):

Landscaping was a priority for the project. Approximately to 800 000 plants were planted along the route. The motorway has a notably wide median, constructed as such to “future-proof” the project and allow for it to be widened in the future. One of the most unique features of the project was the construction of a dedicated bicycle and pedestrian lane parallel to the motorway, providing 40km of path for leisurely use by the public, the longest such path in Australia at construction. A 55 hectare parkland was provided at the southern end of the bicycle route in Abbotsbury, off Elizabeth Drive.

The Westlink M7 officially opened to traffic on the 16th of December 2005, having taken under two and a half years to construct. Upon opening, the route offered motorists;

In alignment with the construction of the M7 Westlink, several roads had to be upgraded. These included (accessed from Ozroads):

- Old Windsor Rd/Norwest Boulevard grade-separated interchange

- Sunnyholt Rd widening (James Cook Drive to Sorrento Drive)

- Quakers Hill Parkway widening: (Hambledon Rd to Westlink M7)

- The integration of the entirety of the Phillip Parkway into the project

- The Horsley Drive widening

- Elizabeth Drive duplication (Windsor Rd to Wallgrove Rd)

- Cowpasture Road duplication (Nineteenth Avenue to Hinchinbrook Creek)

- Hoxton Park Road duplication (Banks Road to Cowpasture Road)

- Bernera Road/Jedda Road/Joadja Road duplication near the motorway

- Kurrajong Road duplication

- Widening the Hume Highway southbound carriageway to four lanes (Camden Valley Way to Brooks Rd)

- Duplication of the Camden Valley Way (M5 to Bernera Road)

Landscaping was a priority for the project. Approximately to 800 000 plants were planted along the route. The motorway has a notably wide median, constructed as such to “future-proof” the project and allow for it to be widened in the future. One of the most unique features of the project was the construction of a dedicated bicycle and pedestrian lane parallel to the motorway, providing 40km of path for leisurely use by the public, the longest such path in Australia at construction. A 55 hectare parkland was provided at the southern end of the bicycle route in Abbotsbury, off Elizabeth Drive.

The Westlink M7 officially opened to traffic on the 16th of December 2005, having taken under two and a half years to construct. Upon opening, the route offered motorists;

- A carriageway freeway linking the M2 Hills Motorway at Seven Hills with the M5 South Western Motorway at Prestons

- 40km of dual carriageway

- Two lanes in either direction

- 18 grade-separated interchanges, including Australia’s first (and only) complete freeway-to-freeway interchange

- 146 bridges

- 56km of noise walls

- A speed limit of 100km/h

- A bypass of 48 sets of traffic lights compared to the alternative route along the Cumberland Highway

Post-Opening and Current Day

The M7 Westlink has been an inspiring example of a successful PPP (Public-Private Partnership), especially in a country where such projects have since gone disastrously wrong (read more here). By 2008 approximately 119,592 vehicles were using any part of the motorway each day. By 2016, this number had increased to 179,000 vehicles.

As a result of the opening of the M7 Westlink, the Phillip Parkway’s legacy lived on; it had been originally conceived as a route linking the F2 Castlereagh Freeway with the F4 Western Freeway, which the route now does as the M7.

The motorway was not originally conceived with a toll in mind, however it was decided before the project begun that it would be operated as a toll road in order to recoup costs to construct the road. Electronic toll gates were installed at all entrances and exits to the road, with a distance-based tolling scheme currently capped at $8.08 (as of August 2018) employed along the road. The motorway is currently owned by Transurban, who sponsored the construction of the motorway. Under the contract originally arranged by the operators of the motorway, the motorway will be tolled until 2048; originally set to expire in 2037, the period was extended in order to cover costs for the NorthConnex project.

The M7 Motorway is one of the few motorways in Sydney that has not suffered from severe congestion, with no major upgrades having been implemented on the road in its 13 year history, and with no significant plans for the road existing into the future. This is owed to the rare example of forward thinking employed by the government in constructing the motorway, arguably not a priority when it was constructed and yet certainly appreciated. The motorway has greatly enhanced connectivity to Western Sydney from the Northern Suburbs, as well providing a speedy bypass of Sydney that allowed traffic along the Cumberland Highway to be significantly reduced.

The M7 Westlink is the single longest section of the 110km Sydney Orbital, as originally proposed in Roads 2000, that allows traffic to bypass urban centres around Sydney. On the opening of the Lane Cove Tunnel in 2007, the Sydney Orbital as envisioned by the plan was completed.

When the NorthConnex opens in 2019, linking the M2 Hills Motorway at West Pennant Hills with the M1 Pacific Motorway at Hornsby, traffic will be able to properly pass between the Pacific Highway and the Hume Highway without encountering any traffic lights.

Eventually, in the distant future, the Westlink M7 may be superseded by the opening of an Outer Sydney Orbital. Such an orbital could provide a wider bypass of Sydney. Commonly dubbed the M9 Outer Sydney Orbital, preliminary designs have already been released for the motorway. For more on the project, visit this page.

The M7 Westlink has been an inspiring example of a successful PPP (Public-Private Partnership), especially in a country where such projects have since gone disastrously wrong (read more here). By 2008 approximately 119,592 vehicles were using any part of the motorway each day. By 2016, this number had increased to 179,000 vehicles.

As a result of the opening of the M7 Westlink, the Phillip Parkway’s legacy lived on; it had been originally conceived as a route linking the F2 Castlereagh Freeway with the F4 Western Freeway, which the route now does as the M7.

The motorway was not originally conceived with a toll in mind, however it was decided before the project begun that it would be operated as a toll road in order to recoup costs to construct the road. Electronic toll gates were installed at all entrances and exits to the road, with a distance-based tolling scheme currently capped at $8.08 (as of August 2018) employed along the road. The motorway is currently owned by Transurban, who sponsored the construction of the motorway. Under the contract originally arranged by the operators of the motorway, the motorway will be tolled until 2048; originally set to expire in 2037, the period was extended in order to cover costs for the NorthConnex project.

The M7 Motorway is one of the few motorways in Sydney that has not suffered from severe congestion, with no major upgrades having been implemented on the road in its 13 year history, and with no significant plans for the road existing into the future. This is owed to the rare example of forward thinking employed by the government in constructing the motorway, arguably not a priority when it was constructed and yet certainly appreciated. The motorway has greatly enhanced connectivity to Western Sydney from the Northern Suburbs, as well providing a speedy bypass of Sydney that allowed traffic along the Cumberland Highway to be significantly reduced.

The M7 Westlink is the single longest section of the 110km Sydney Orbital, as originally proposed in Roads 2000, that allows traffic to bypass urban centres around Sydney. On the opening of the Lane Cove Tunnel in 2007, the Sydney Orbital as envisioned by the plan was completed.

When the NorthConnex opens in 2019, linking the M2 Hills Motorway at West Pennant Hills with the M1 Pacific Motorway at Hornsby, traffic will be able to properly pass between the Pacific Highway and the Hume Highway without encountering any traffic lights.

Eventually, in the distant future, the Westlink M7 may be superseded by the opening of an Outer Sydney Orbital. Such an orbital could provide a wider bypass of Sydney. Commonly dubbed the M9 Outer Sydney Orbital, preliminary designs have already been released for the motorway. For more on the project, visit this page.

links

- http://www.cpbcon.com.au/projects/westlink-m7-2/

- http://www.cpbcon.com.au/projects/westlink-m7/

- https://www.cimic.com.au/our-business/projects/completed-projects/westlink-m7

- https://www.roam.com.au/using-westlink-m7/about

- https://www.roadtraffic-technology.com/projects/westlink/

- http://www.rms.nsw.gov.au/projects/key-build-program/building-sydney-motorways/m7.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Westlink_M7

- http://ozroads.com.au/NSW/Freeways/M7/m7.htm

- http://ozroads.com.au/NSW/RouteNumbering/Deccomissioned%20Routes/SR61/philippkwy.htm

- https://www.skyscrapercity.com/showthread.php?t=129317

- https://www.roam.com.au/using-westlink-m7/about/toll-pricing

- http://www.ozroads.com.au/NSW/Highways/Cumberland/history.htm

- http://www.smec.com/en_au/what-we-do/projects/Westlink-M7

- http://www.jacksonteece.com/projects/western-sydney-orbital-m7

- http://apps.westernsydney.edu.au/news_archive/index.php?act=view&story_id=1445

- http://infrastructureaustralia.gov.au/policy-publications/publications/files/Review_of_Major_Infrastructure_Delivery_PWC.pdf

- https://thewarrencentre.org.au/urbanreform/connectivity-case-study/the-m7-motorway/

- http://www.abc.net.au/news/2005-12-16/pm-set-to-open-15b-westlink-m7/762502

- https://www.treasury.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017-02/Westlink_M7_contr.pdf